Reviews

“It is a pleasure to welcome this account of life in Afghan refugee camps by an observer dedicated to easing as well as reporting the traumas of exile and the hardships of making do in crowded, alien environments. Over the long years when the displaced Afghan population gained unhappy repute for being the world’s largest concentration of refugees from a single country, a profusion of critiques, official reports, and analyses were written. None focuses so dramatically on the emotional human dimension as do Jean Heringman Willacy’s diaries. The Keeper of Families is a notable addition to the study of displacement which, sadly, continues to be a major human issue of growing proportions. New Jean-type reporting is needed..”

—Nancy Hatch Dupree (1927-2017),

Internationally acclaimed historian and authority on Afghanistan,

Founder of the Afghanistan Centre at Kabul University

Pacific Book Reviews

Title: The Keeper of Families: Jean Heringman Willacy’s Afghan Diaries

Author: Sue Heringman

Publisher: AuthorHouseUK

ISBN: 78-1-7283-8064-3

Pages: 372

Reviewed By: Susan Brown

Pacific Book Reviews

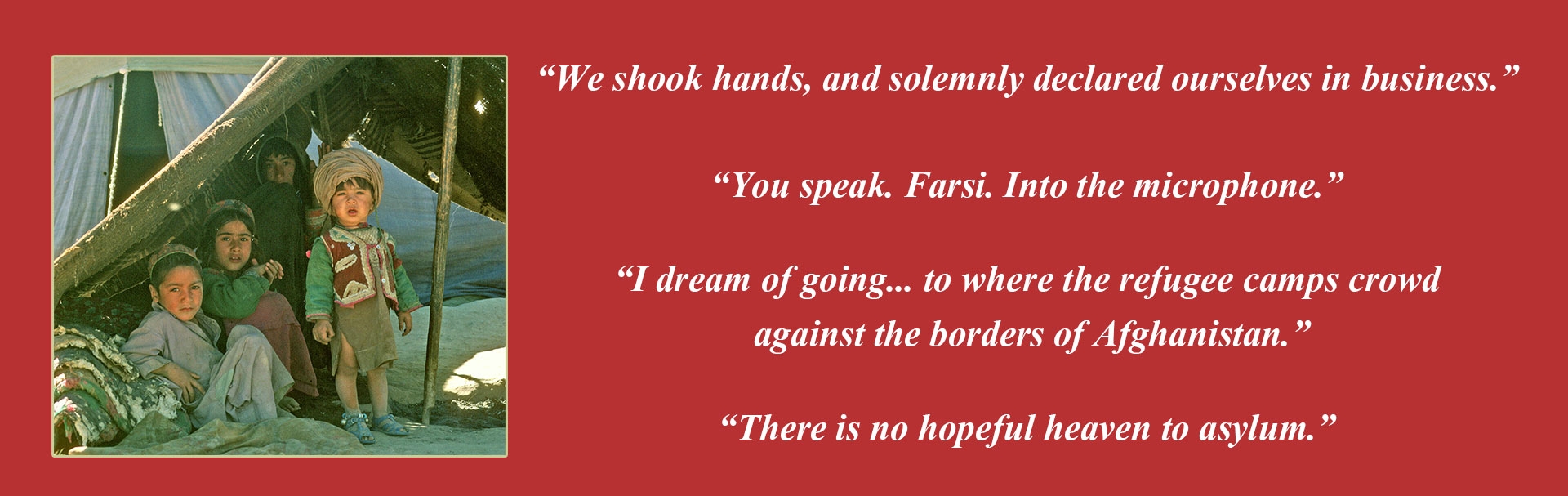

Those who give of themselves in service to people less fortunate leave a legacy of friendship and goodwill to the individuals who have benefited from that type of heart-warming kindness. American Jean Heringman, the courageous woman of this memoir, didn’t set out to create such a legacy, but through her advocacy for her adopted, extended Afghan families, that is exactly what happened.

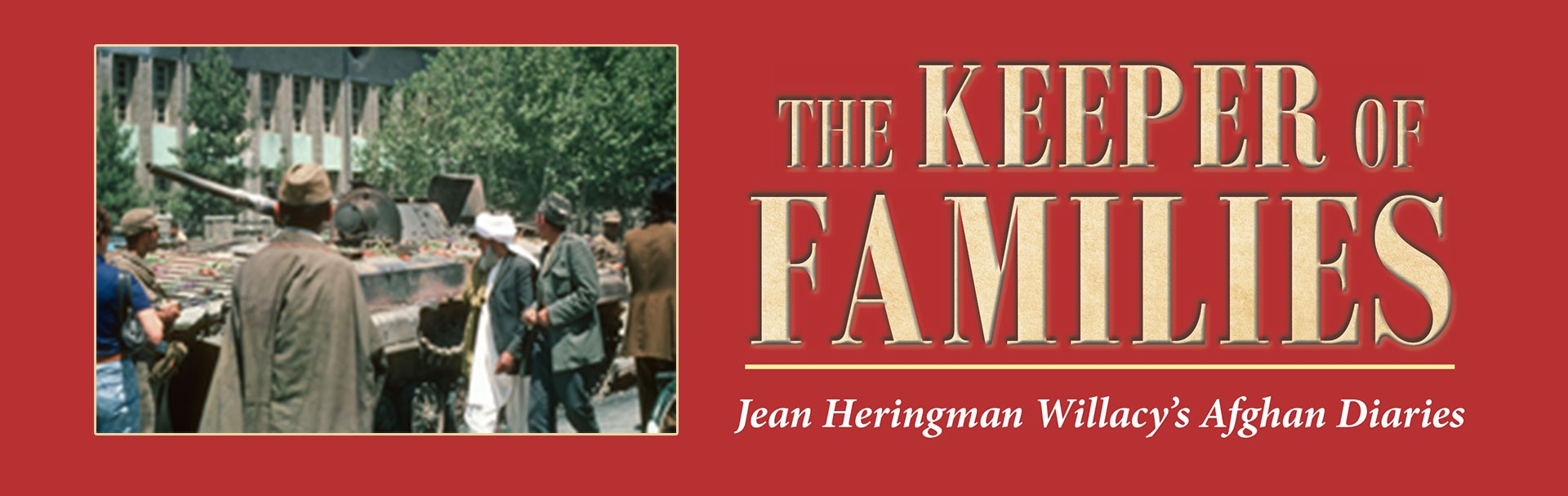

What begins as a business foray, buying and selling traditional handmade Afghan clothing, brings Heringman to Afghanistan. As she travels the country, she comes to love and cherish the friendships she makes. In the aftermath of a Soviet invasion, that affection transforms her into a champion of the beleaguered and oppressed refugees fleeing their homeland throughout the ensuing occupation. The accounts of Heringman’s time in Afghanistan have been curated by her daughter from a collection of diaries, live audio tapes, pictures and notes from interviews with men, women and children both pre- and post-Soviet occupation. In her initial travel notes, there are charming insights into the country’s colorful culture.

Her perceptive writing is filled with lighthearted detail. As a tourist in Kabul she notes, “There is a bicycle almost hidden from view because of the big load of green onions that is strapped to the peddler’s back. And everywhere there are little carts piled high with all different kinds of fruits. Seated on top of them are the vendors. They curl up into a teeny, weeny space; their legs tucked underneath them, and perch like so many birds hovering over their goods.”

The vibrant mélange of sights, sounds, aromas and infectious buoyancy of the locals she meets is dramatically changed by a military coup that allows the Soviets into the fabric of the country. In an instant, Heringman is thrust out of her role as friend and confidante into one of spokeswoman, crusader and tireless fighter for displaced Afghan refugees whose lives have been upended. She observes, “Exile has forced many refugees to abandon their traditional tribal ways, and consequently they suffer a loss of pride, identity, and self-respect.” Her mission to shine a light on this tragic situation dominates the remaining years of her life. She states, “Their stories must be told to show the world that it is not merely enough to have escaped tyranny and oppression. Promises must be kept. Those who preach compassion must also show it in a practical way. Political expediency must never be allowed to override moral obligations.”

Of course, this narrative of human displacement due to war is as relevant today as it was at the time of Heringman’s involvement in Afghanistan. The current refugee crisis in that country, as well as across South Asia and the Middle East is a well-documented crisis. Books like this one help us see the cost paid by those who through no fault of their own, have been forced to walk away from their native land and, in the process, inspire us to help.

In Heringman’s own words, “Books are not written about people like us. But it doesn’t matter, for we know in our very souls what good we have given to others.” I highly recommend reading this memoir. I also look forward to reading more of Sue Heringman’s writing. You will not be sorry you picked this book up and started this journey with the author.

The US Review of Books

The Keeper of Families: Jean Heringman Willacy’s Afghan Diaries

by Sue Heringman

AuthorHouse UK

book review by Kate Robinson

“Enthralled by mountains, Jean journeyed dauntlessly through the countries spanned by the Himalayas.”

After Willacy’s death in 2004, her daughter, Sue, took on the momentous task of compiling and publishing this intimate, cohesive record of her mother’s extraordinary experiences. This historical yet timely biography, composed of drawings, journal entries, letters, personal notes, photographs, speeches, and transcripts of tape recordings, is a tribute to Willacy’s life and legacy and to the indomitable people of Afghanistan.

An American housewife displaced by divorce in the 1960s, Willacy chose an adventurous new life in Afghanistan in 1967 as a visiting businesswoman, importing licorice root and traditional fur-trimmed, embroidered coats favored by hippies in the UK and USA and supplying English language books to Afghan readers. Despite her inexperience in business, she utilized her success to organize an embroidery cottage industry for impoverished widows in Afghanistan’s remote sheep districts. But these carefree years came to a halt in 1978 with the bloody Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Jean’s role suddenly changed from businesswoman to advocate during one of the most brutal refugee diasporas in modern history. She put her photographic and artistic talents to good use while documenting the lives of women and children in Afghan refugee camps in Pakistan and ultimately used children’s art and their personal descriptions of refugee life in successful fundraising exhibitions.

At times, the epistolary narrative by its very nature seems narrow and episodic, but the patient reader interested in the plight of refugees will be rewarded with a vivid look at the difficulties faced by Afghan women as they navigated the decade-long limbo of refugee camps and the confusing asylum applications to faraway Western countries. This volume is a valuable study of a phenomenon becoming all too common as the contemporary migration and refugee crisis currently engulfs 68 million people worldwide.

RECOMMENDED by the US Review